In memory of my parents, Carl Spencer Sevy and Maude Malmquist Sevy.

Chapter 1:

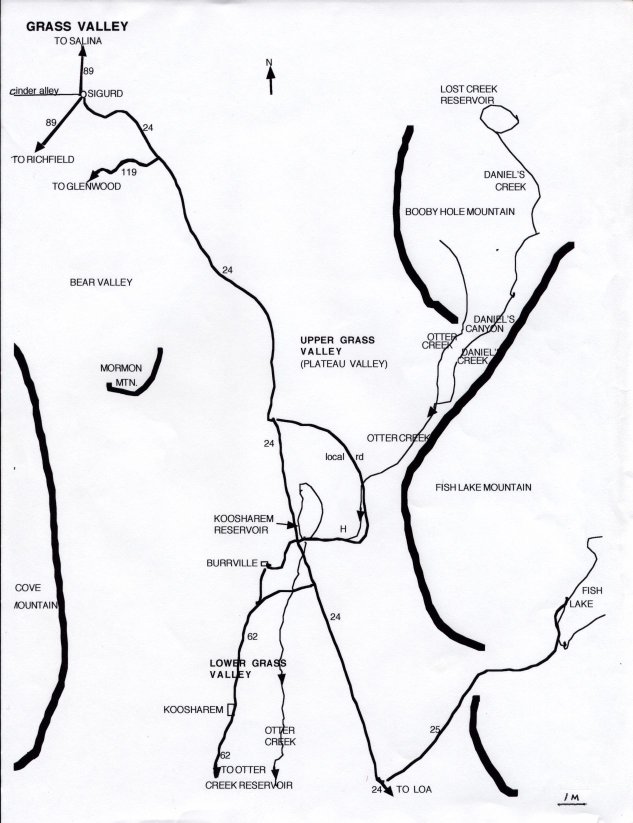

GRASS VALLEY

The early sunlight reflected off the clear surface of the water on the west side of the lake, bordered by the low sagebrush-covered hills. On the east side, in the shadow of Booby Hole and Fish Lake Mountains, the mist was slowly lifting and the surface of the lake was broken by the multiple ripples caused by the rising of hungry trout. The fat, white-faced cattle were peacefully feeding in the pasture bordering the lake, and there, lazily grazing among them, was Pet, the big bay mare with white stocking feet. It was a beautiful scene to behold on nearly every summer morning as one looked out the kitchen window of the little house there in the pasture.

This was Grass Valley, home of my very first memories. The very first scene I can recall was that of Lonzo Dickenson, in chaps and spurs, racing toward the house from the corral, yelling very loudly, “My God, the dogs ate the coyote bait! We better bleed them fast or they’ll die for sure.” Then he cornered one of the dogs in the little side-shed of the house and with a big hunting knife which seemed to appear in his hand as if by magic, he whacked off two thirds or more of the poor dog’s tail! The dog ran yelping and bleeding toward the mountain, while Lonzo grabbed the second dog and repeated his ghastly surgery. I don’t remember what happened to those short tail dogs, whether they lived or died, but I do remember that scene – very vividly! After that I showed Lonzo a great deal of respect, and also gave him a wide berth whenever he seemed to be headed in my general direction.

Grass Valley was also home to four other ranchers situated between the east shore of the lake and the mountain, and all four of them envied my father for having a ranch hand like Lonzo. He really did have many other talents and came from a very accomplished family. His uncle Oate Dickenson, for instance, was the best mountain lion hunter in Southern Utah, and the protection he afforded the ranchers won him a lot of respect among them. He would sometimes track a lion for a week or more before he could get a bead on it with his 30/30 rifle. He probably also shot more coyotes than were killed by the poison bait the ranchers put out. Coyotes and lions, and sometimes bears, were a real hazard for livestock, and both government and ranchers paid handsome bounties for them. Nowadays many would regard this as a horrible intrusion against nature. Back then I don’t think as much attention was given to nature’s balance – of course, even now man is usually not regarded as a legitimate participant in nature’s overall plan, though I don’t know why not.

Soon after I was born my mother and I went to live with my father in the little house at Grass Valley. Of course I remember nothing about the first couple of years, but my aunts, Vera and May Malmquist, later told me a few stories about those early years. The nearest town of maybe a dozen families in all – Andersons and Burrs mainly – was Burrville, about four miles away. My mom used to travel there in a buggy; it was on a dirt road just across the dam, over the hill and down into the next little valley. She had made a deal there with one of the women to do our laundry, including my diapers. The woman had flowing water and a washing machine with a hand wringer, whereas my mom had only the creek and a tub and scrub-board. There was no store or other services in Burrville, but there was a general store, and also a Mormon church and a School House, in Koosharem, a small town a few miles farther on. However, most of our supplies were purchased in Sigurd rather than Koosharem. Even though Sigurd was farther away, it was where my mom’s folks lived and also the home of the Sigurd Merc., a general store partly owned by the Sevy family. My aunts came up from Sigurd to visit us every couple of weeks during the summer. Sigurd was about twenty miles down the canyon, so it was a long trip for them in a horse-drawn wagon, up the old gravel road leading eventually to Fish Lake, a fishing resort about fifteen miles farther up the canyon just beyond the crest of Fish Lake Mountain in Fish Lake National Forest. My folks went there once on vacation with friends, Ky and Velva Branch from Richfield, traveling by wagons loaded with camping gear, grub boxes and baby blankets. My mom later showed me a snapshot of Clare Branch and me each in our own jumper suspended from the branch of a big quak’naspen (quaking aspen tree) beside our canvas tent. Clare and I were the same age and too young to crawl or walk. Our mothers had been best friends for years and remained so until they died more than fifty years after that vacation. Clare and I also became good friends, although we haven’t seen each other often since school days.

Later on, as preschoolers in Grass Valley, my sister Ruth and I spent many pleasant days playing in the corrals and sheds around our little house. It’s good we had each other for company because there were hardly any other children around within walking distance to play with. Also, except when her sisters came to visit, my mom’s life was quite lonely too. She read a lot and also listened to records on her hand-wound phonograph. My father spent most of his time herding the sheep and tending cattle on Booby Hole and Fish Lake mountains. We did have one neighbor family, the Lipseys, within walking distance but they were not very friendly. They had a son, Lloyd, several years older and much bigger than I. He would come over to play with me and then, instead, would beat up on me until my mom would stop him. Eventually my dad made it plain to him that he was not to come over to our house to play any more. I remember Lloyd’s dad, who was called “Boss”, as a white haired, mean looking man who seemed to be mad at everybody, including his wife.

Later, Boss would come to charge Charlie Burr, with whom he had long feuded over water rights, with mayhem, and in return Boss would come to be charged with Charlie’s murder. Oh yes, the Lipseys and the Burrs and their feud managed to provide the Valley lots of exciting news!

Despite the beatings by Lloyd, and the violent tempers in families around us, I still have very fond memories of our life in Grass Valley. I can still see the ripples on the lake at dawn, and smell my mom’s homemade bread in the oven of the old wood-burning stove in the kitchen and feel the joy of seeing my dad come riding his horse into the corral at dusk. My love of horses started there. I was given my first horse there before I turned five; her name was Pet, the big bay mare with the white stocking feet. Many years later my mother showed me a photograph of me at the age of five, sitting in a little saddle on top of my big bay mare. Even though it was a boy’s saddle, my legs were too short to reach the stirrups so they were tucked in between the leather straps. I had on a big cowboy hat and cowboy boots and a cowboy bandanna around my neck. I couldn’t actually see my face but I took my mom’s word that it was I. My second horse was Pet’s first colt. She was a beautiful sorrel mare, named Juana, born in Colorado. I was older then, all of six, but we sort of grew up together. I was the first person ever to ride her, and I really can’t remember her trying to buck me off, as horses are supposed to do when they are first broken to ride. But more of her and our wild rides later on.

Grass Valley is well named with its carpet of grassy meadows watered by the steams coming off the Booby Hole and Fishlake mountains on the east and Cove mountain on the west. The lake became known as the Koosharem Reservoir after the construction of an earthen dam to allow greater storage of water from mountain streams. The part of the valley above the dam is sometimes referred to as Plateau Valley, but I think of it as the upper or northern part of Grass Valley. Koosharem (an Indian name) and Burrville, and the farmlands surrounding them, are part of the larger Grass Valley below the dam. All of them, and also Sigurd, are located in Sevier County named for the Sevier River, which owes its origin to runoff from the mountains near Bryce Canyon. The waters from Grass Valley join the Sevier River near Circleville, the home of Butch Cassidy. Grass Valley is not the address of a town nor a particular postal address on the map. It is just a valley – a beautiful valley surrounded by beautiful mountains.

Map of Grass Valley

Roger and Ruth at play in Grass Valley!

Chapter 2:

FROM SEAVEYS ON THE ISLES OF SHOALS TO SEVYS IN SIGURD

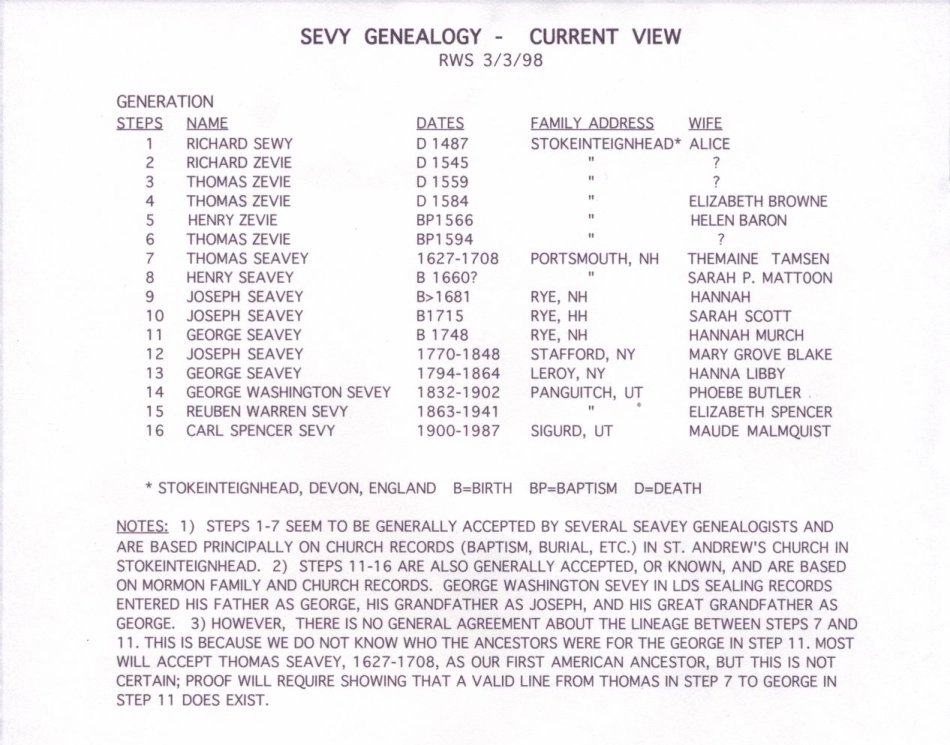

Being a Mormon, my father was quite naturally interested in the Sevy family genealogy. One reason Mormons like to trace their ancestors is their belief in the hereafter, where they and their families may continue to exist happily together for eternity. Thus, when a couple is married in a Mormon temple the bond is for eternity. In addition, although one is not baptized into the church until the age of eight, one can thereafter also be baptized for non-baptized dead relatives so they too will be assured of entering the true Kingdom Of God. So my father’s efforts to trace his ancestors were very understandable, but only partially successful. I remember him telling me that the first Sevys to land in America were two brothers who came from England many generations ago, and my Dad’s younger sister, Aunt Alice, told me later that their father (my grandfather) said they had landed on an island off the coast of Maine. My father also knew that the first ancestor to arrive in Utah was my great-grandfather, George Washington Sevey. He was born in LeRoy, Genesee County, NY in 1832 and headed west to join the California gold rush in 1849. He got sick along the way and had to be left behind, on the trail, by the group he was traveling with. Luckily, he was found by a Mormon travel party who took him along with them to the Great Salt Lake valley. He later became a loyal Mormon and settled the town of Panguitch, Utah under directions from Brigham Young. Since my great grandfather’s arrival in Utah, the family history is, of course, well known. However, for the time before two Seaveys landed on an Island off the coast of Maine, and the time between their arrival in America and my great grandfather’s arrival in Utah, there are some interesting gaps. More recently, my sister Ruth Sevy Dragg has renewed the study of our Sevy genealogy and the following is a brief summary of what she has learned.

Our first ancestors in America were William and Thomas Seavey. William, a sea captain with a ship under a British shipping company owned by a man named Mason, was the first to arrive. He landed in 1632, during the reign of Charles I, on one of the Isles of Shoals off the coast of what is now Maine and New Hampshire. Thomas, who was probably William’s nephew rather than brother, came a few years later. One of the Isles of Shoals became known as Seavey’s Island and was owned by Captain Stephen Seavey, a descendant of William. It is still known as Seavey’s Island among the locals in Portsmouth. !n 1866 it became part of the Portsmouth Navy Yard; in the Spanish-American war it was used as a prison for Spanish officers and sailors.

William and Thomas Seavey, the first Seaveys in America, came from a little town, Stokeinteignhead, in Devon, England; most of the early family records were found there in St. Andrew’s church. William, the first to land in America, was born in 1601 and had an older brother, Thomas Seavey, born in 1594; they were the sons of Henry Zevie and Helen Baron Zevie. Thomas Seavey had a son, also named Thomas, born in 1627, who was the second Seavey to set foot in America and, by all accounts, the first American ancestor of the Sevys in Sigurd, (and also, of course, of many Seaveys, Seavys, and Seveys in New England, New York and elsewhere). What are missing in the way of proofs are official vital records, or records provided by direct family communication, for the correct lineage between Thomas Seavey of Portsmouth, NH in the late 1600’s and our Seavey ancestors in Genessee County, New York in the early 1800’s. The last, presumably direct, testimony within the George Washington Sevey family holds that his grandfather was Joseph Seavey, born 1771 in Vermont, and that his great grandfather was George Seavey born about 1750. My sister’s search for the true lineage would perhaps be a little easier if successive generations of our ancestors had left the spelling of the name alone! In any case, it is a very long way from Seavey’s Island in the Isles of Shoals in the 1600s to the Sevys in Sigurd in the 1900s!

The Sevy family genealogy, from the 15th century to the 20th.

Chapter 3:

SIGURD TOWN

While growing up, one of my favorite fantasies was that our little town of Sigurd must have been named after the ancient Scandinavian hero, Sigurd, who was the son of Sigmundr and who slew the ferocious dragon, Fafnir. We certainly had enough Scandinavians around – Andersens, Jorgensens, Nelsons, Nielsens, Jensens, Malmquists, Iversens – to suggest such a name. So, it might have been true. But, alas! It was only fantasy.

Sigurd started out as the south part of a two part, north and south, pioneer town which was originally called Vermillion. It was called that by Brigham Young because of its bright red soil. The two parts were separated by about a mile, in which there was a wild forested area called the willow patch. The south part was sometimes referred to as uptown and people in the north part were often afraid to walk there because of the many wild animals in the willow patch. But when the time came to petition the government for a post office, the people were told that the name Vermillion already belonged to another town. So the name Sigurd was proposed as the name of the post office, and hence the town. I still knew Vermillion as that other town a mile or so to the north of Sigurd, and the kids living there still called their town “Vermillion”. They really did appear as two small towns along highway U.S. 89, about a mile distant from each other, and they behaved as separate towns, except for attendance of the kids in the single school, located in the part I’m calling Sigurd. The kids in Vermillion were bussed (maybe hauled is a more descriptive word) to the school in Sigurd for grades 1 through 6.

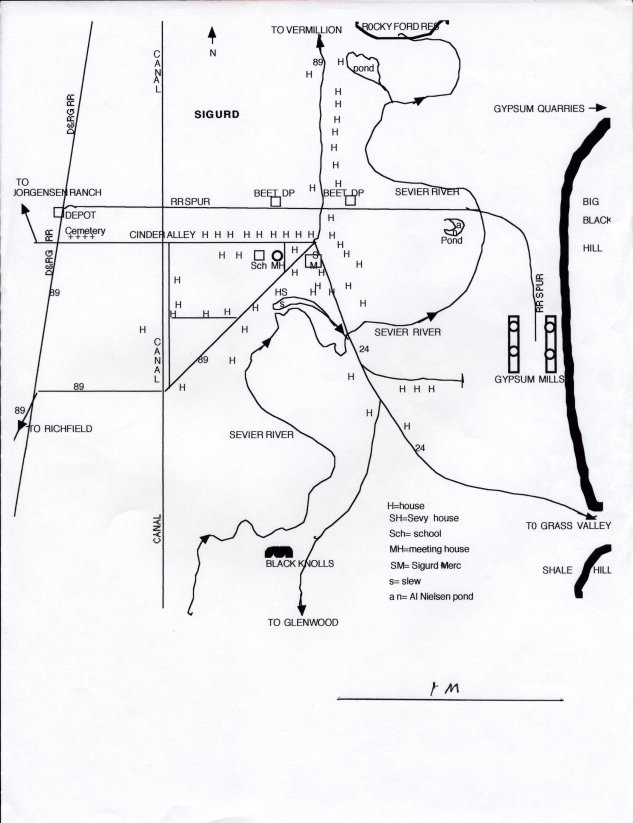

This is a view of Sigurd as I saw it and recalled it in my memory from about 1927 through 1941; others may have seen it and recalled it differently. I know from two other written descriptions of events there that some people did see a very different town from the one I saw. The difference seems to be due mainly to the role of religion in forming these images. Sigurd started as, and still is, a Mormon town. I grew up in the middle of town, where life seemed to be less religious and quite different from that on either side. The difference is perhaps reflected by the names we in the middle gave to the two ends. We referred to the south end as “Bishoptown” because most of the church ward bishops seemed to come from there. We referred to the north end as “Gurrville” because many of them were members of, or related to, the Gurr family, which also seemed to be more involved in church affairs. Now these were not clear divisions, because there were some heavy church goers and nongoers in each area of town. But this gives you some idea of the differences. However, if we had each drawn a map of town, the maps would have looked very much alike and you would say they were maps of the same town. But, if we had given a description of each building in town, you might begin to wonder if they were the same town. And if we had described the behavior of the people, you’d know they weren’t the same town at all. So you must remember that this view of Sigurd is strictly mine during my growing up period.

The first full-time resident of Sigurd (originally Vermillion) was my great grandfather on my mother’s side, Henry Nebeker, who moved from Glenwood, another Mormon town to the southeast, to build a stone house between the two Black Knolls on the east side of the Sevier River in 1871. There was a large spring at this sight which drained into the river. In my days in Sigurd, the river at this point was a favorite fishing hole for carp, suckers, bass and a few trout. Also the Black Knolls was a popular spot for playing “Cowboys and Indians”, even though it was somewhat dangerous because of the numerous rattlesnakes among the many black rocks. We also found many Indian artifacts (arrow heads, picture writing) on the knolls. As a young girl my grandmother Malmquist (then Dora Nebeker) used to herd the family cows on horseback in the grassy meadows on either side of the river. My grandfather August Malmquist once told me that he first fell in love with her when he saw her as a teenager riding side-saddle on a full gallop across the meadow, with her long brown hair blowing in the wind. His family had moved to Gunnison, Utah from Sweden in 1874, and then farther south to Sigurd a few years later.

The Black Knolls provided a prominent landmark for the southeast corner of Sigurd, about a mile from the center of town. Directly east of the town’s center, across the river, was the big black hill. This was also a favorite playground for playing “Cowboys and Indians” or “robbers and sheriffs”, often with all the kids on both sides on horseback. We didn’t use real guns though; we used wooden guns which shot heavy, knotted, rubber bands cut from inner tubes of tires held taught by clothespins, until released by a press of the trigger. Once hit by one of these you were declared dead and out of the game. The winning team was usually the one which could make the best far-shooting guns! Beyond the big black hill were many hills of a lighter color which contained large deposits of gypsum, used to make plaster. The plaster mill was at the foot of the big black hill on the side facing town. This was the biggest employer of men in town; nearly all the others were farmers.

The Sevier River ran from the Black Knolls north past the mill and the big black hill and wound its way on the east side of town as it made its way to the Vermillion reservoir. This river is a lifeline for many towns like Sigurd, not only in the Sevier Valley, but also farther upstream and downstream. One of my uncles, Orvin Malmquist, was a journalist for The Salt Lake Tribune, and he once described it as one of the most used rivers in the world. In nearly all years it is in fact all used up before it can empty into Sevier Lake, which is usually a dry lake, in western Utah near Delta. The river is, of course, used for irrigation. Mormons are absolute wizards in irrigation, and in my day Irrigation Engineering courses at Utah State University (then Utah State Agricultural College), attracted many students from arid countries around the world. As Sigurd kids, however, we put the river to many other uses. It provided many favorite swimming holes, fishing holes, duck hunting marshes, pelican roosts, muskrat trapping areas, rapids to shoot and served as our own Mississippi for lazy summer rafting and dreaming. Wintertime skating on the other hand was better on ponds and slower running irrigation canals.

On the west side of Sigurd were the reddish, purple, multicolored mountains which had given Vermillion its name. These were penetrated by the North and South Canyons which opened on to the valley floor which was cut from south to north by two irrigation canals, one near the west edge of town and one much further up toward the foothills of the west mountains. Sometimes, after cloudbursts up in the mountains, beyond the sight of town, large floods would come roaring out of these canyons very suddenly and flow along the roads in town. They would also have washed out the canals and their banks, except for one thing: the construction of spillways which conducted the floods over the canals. The floods also left a lot of downed trees from the mountains not too far up from the mouths of the canyons. This made the canyons a favorite place for the townspeople to load up their wagons with firewood in the fall. Pine logs rich with pitch kept many a house warm in the middle of winter. And woodpiles in the back yards gave us plenty of opportunities to strengthen our muscles swinging axes.

Highway U.S. 89 ran from Vermillion in the north up through the middle of town toward Richfield, the County Seat, in the south. It was asphalt covered and was the main street in town. Near the center of town it was intersected by highway 24 which headed southeast, across the river, past the mill and up the canyon between the big black hill on the left and the big shale hill on the right. This was the road to Grass Valley and Fish Lake. Just south of their intersection both highways 24 and 89 also intersected a gravel road right in the middle of Sigurd, which we called Cinder Ally, after it was once covered with cinders, and which ran west through town toward the cemetery and west mountains. Near these central intersections were the church, a general country store and a gas station.

The homes in town were scattered along both sides of highways 89 and 24 and Cinder Alley; a few were on other side roads by the mill on the east or along the canal on the west; two were some distance from the center, one being the Jorgensen ranch, beyond the cemetery toward the western mountains, and the other the stone home by the Black Knolls. By my count there was a total of 51 homes; given an average family size of about 6, that would give us a population of 306, and that’s about what it was while I was growing up. The most significant public buildings in town were the Meeting House, the School and the general store, the Sigurd Merc.

The Meeting House was easily the most important. It was originally built of black stone, in about 1911, but was later covered with stucco, made possible by a donation of unmarketable plaster from the plaster mill following a fire. The Meeting House was constructed to be the Mormon Chapel, but dedication was delayed until it became free of debt. Actually, “Meeting House” is a more accurate description, for it served as much more than a place of worship! It was also a banquet hall, a dance hall, a theater, a basketball court and a general meeting place for both young and old. Except for school, all important meetings and get-togethers took place in the Meeting House. I can remember going to my first dance there; I can remember seeing my first silent movie there; I can remember going to my first big banquet there; I can remember Tex Barron, Max Anderson and me doing our tap dancing routine on stage there as part of a July 4th celebration; and I can remember having so many more exciting times there. I’ll never forget that Meeting House. Of course I also knew it as a church where I went nearly every Sunday.

The School House was a two story red brick building which had three class rooms, one for grades 1 and 2, one for grades 3 and 4, and one for grades 5 and 6. The classes were small, so, despite the admixture of grades, we each got plenty of attention and good instruction. School was also lots of fun and I think all the kids liked being there very much. Judging from the colleges and careers my class mates went on to, I think their education was generally good.

The Sigurd Merc. was a general country store selling every thing from soup to nuts – shovels, corsets, pork and beans, ice cream, firecrackers, bullets, high-button shoes, Levis, candy, fishing tackle and much much more. And there were gas pumps out front and rock-salt sheds out back. My uncle Claude ran the store, in addition to his veterinary practice, for a few years before the depression and I remember it as a very busy place. My father ran it later for a few years during the depression, and at that time it was called the Sevy Merc.

During the depression the store was not a money making proposition, partly because a lot of people were carried on credit and many of the bills were never paid. I remember one family had an accumulated bill of well over a thousand dollars, a lot of money in those days. My father pleaded with the head of house to pay up, but to no avail, even after the man made a lot of money in California at a race track where his son was a famous jockey. I also remember that the store was robbed more than once, usually by breaking and entering at night. There was even a period when my father slept nights in a back room at the store with a thirty-eight pistol under his pillow. I don’t remember anyone trying to break in during any of those nights, and I’ve always suspected the robbers were local and knew when the store was vulnerable. But of course nearly everyone else in town, including my father, knew the robbers had to be strangers passing through. In those days there were quite a few needy strangers passing through town. We called them tramps, but not to mean anything disrespectful. They were just tramping through on foot, looking for something more worthwhile to do. They often came to the door of the house asking if they could do anything, like chopping firewood, for something to eat. My mom gave them many sandwiches made with thick slices of her homemade bread. And neither she nor I ever suspected them of the night-time robberies at the store. One of those robberies involved hacksawing the lock on the gas pump, and, from snatches of conversations overheard among some of the older guys in town, I was pretty well convinced that the ones responsible for that theft were not strangers passing through. But could such lawlessness really exist in Sigurd? I’m sure it did to some extent. Even teenagers, in search of goodies for picnics and cook-outs, were sometimes known to swipe a few cherries, apples, watermelons and fryer chickens from local farmers. On the other hand, strange as it seems now, people in Sigurd at the time never locked the doors to their houses, even when away for days at a time. And, to my knowledge, the houses were never violated. My mother was Secretary of the Relief Society, within the Church, and kept their petty cash fund in a shoebox in her closet. There was never any money stolen from that shoebox.

Map of the town of Sigurd

Roger in the back yard of the Sevy house

Roger at work in the beet fields

Leah Carter, Gerry Sevy and Marilyn Black

Sned in front of the old church

The Sevy Mercantile in the 1930’s

The old school house

The Jumbo Plaster Mill

Leah Carter and Gwen Manwill in the 1940’s

Emma Sensen’s house in the 1990’s

50th high school reunion, May 1991

Front: Hal Anderson, Roger Sevy

Back: Dereese Dastrup, Darrol Robison, Mary Evelyn MacMillan, Merill Gurr

Chapter 4:

MAYHEM AND MURDER IN THE VALLEY

Boss Lipsey and Charlie Burr were middle aged ranchers who had been feuding for what seemed like their whole lifetimes. They both lived in Grass Valley , Charlie in Burrville and Boss in an old stone house just beyond the Sevy ranch, up toward the mouth of Daniel’s canyon. They were crotchety old men who didn’t seem very friendly to anyone, least of all to each other. Charlie was always sullen and frowning, while Boss was always ranting and raving. Boss seemed to know the bible by heart and quoted it often, though he claimed to be an atheist. He was always sermonizing.

The reason for their feud was water rights. Each accused the other of stealing his water for irrigation. In Utah much of the land is useless for agriculture without irrigation, and a fairly complex system of water companies has evolved wherein farmers and ranchers purchase shares, along with a land purchase, which entitles them to the use of so many shares of the available water. So it is not uncommon to have disputes about who is using whose water. Such was the case with Boss and Charlie who were continually fighting over their water rights. One day in one of their pastures below the earthen dam of Koosharem Reservoir, Boss accused Charlie of stealing some of Boss’s shares of water, and a fight ensued. Unfortunately, they were both armed with their shovels, tools ordinarily used to control the flow of water through a series of ditches and furrows, but which are fearsome weapons when used in a fight. When the fight was over, Charlie had won and Boss was minus one eye. That’s the mayhem part of the story. Of course suits and court battles followed and animosity continued on an even more hateful scale.

A year or so later Charlie was doing his usual thing, herding his cattle and tending to the irrigation of his pastures, while Boss mostly stayed at home, with a patch over his right eye, sulking. There had been no more fights and everything seemed quiet enough, but you could almost feel the heat between the two families. Then one evening, after supper, Charlie, in his usual custom, saddled his horse and drove his cows to the north pasture. He didn’t know he was being watched by Boss as he started along the well trodden trail toward the pasture. It was about dusk when he was riding back along the same trail. Just before passing a big choke cherry bush, out stepped Boss with a big twelve gauge shotgun pointed straight at him. We don’t know what Boss said to him before he pulled the trigger, but, from what he said later about seeking revenge, we can imagine it was something like,”OK you bastard, here’s one I owe you!”. And that’s the murder part of the story.

I don’t remember Charlie being arrested or punished for mayhem, but Boss was surely arrested, tried and punished for murder. The trial was held in the Sevier County Seat at Richfield, and got lots of attention. My uncle, Ferd Erickson, was the prosecutor and my dad’s cousin, John L. Sevy, was the judge. It didn’t take the jury long to find Boss guilty of first degree murder and John L. sentenced him to life in the State Prison. His family kept trying to get him paroled, but each attempt was angrily opposed by Charlie’s family. As far as I know, Boss died in prison. It was the only murder in Sevier county that I ever knew of. One murder in very sparsely populated Grass Valley must have made it the year’s murder capital of the country. At least that’s what Uncle Ferd theorized. I lost track of both families with the passage of time but did learn that Boss’s son Lloyd later served as the Town Marshal of Sigurd.

Chapter 5:

THE RIVER

Our beloved Sevier river, which provided lots of fun and adventures for the kids in Sigurd, is very important to the welfare of southern Utah. It owes its origin to runoff from the snows on the mountains in the vicinity of Bryce Canyon. From there it wanders north for a couple hundred miles, linking several reservoirs along the way, and then turns abruptly and heads southwest to end in Sevier Lake about forty miles from the Nevada border.

En route the river provides a lifeline for a number of towns ranging in size from a few hundred to a few thousand people, and was a favorite recreational site for hundreds of kids. From Panguitch, the town nearest Bryce Canyon which was settled by my great grandfather, it flows north through Circleville, the home of Butch Cassidy, to the town of Junction where it receives Otter Creek which delivers the runoff from Boobyhole, Fishlake Mountain, and Cove Mountain, the mountains around Grass Valley. Then it winds its way north past the Big Rock Candy Mountain, through Marysvale canyon, to Richfield where I went to high school. It then flows northeast through Venice, past the Black Knolls to Sigurd and thence into the Vermillion Reservoir.

From the reservoir the water, under a considerable head of pressure, flows very swiftly through huge tubes on the bottom into the river below, then continues on its meandering, northward journey past Salina and Gunnison into the Sevier Bridge Reservoir (Yuba Lake). From there it continues north for a short way, but then loops southwest to pass Delta and finally empties into Sevier Lake.

On some maps Sevier Lake appears as a rather large lake. However, most of the time Sevier Lake is a dry lake, without water; the river is all used up for irrigation before it ever reaches its lake! Along its course the river does receive water from many smaller tributaries, but this seldom exceeds the amount used to fill the reservoirs and canals for irrigating the farms. Once in a while, as in 1985, there will be more water than needed and the reservoirs and river will overflow and cause flooding; but this is a rare occurrence. Without this marvelous little river Southern Utah would be much less green and fertile, and my generation would have had much less fun growing up. The river and its connecting tributaries, ponds, reservoirs and marshes provided a perfect playground.

For the few miles from the Black Knolls to the Vermillion reservoir I got to know this river like the back of my hand, every nook and cranny. This stretch of river kept no secrets from me! I knew every muskrat den, every hiding spot along its banks, all the favorite fishing holes, all the favorite swimming holes – even the “secret” one where the girls swam naked – and all the hiding places among the thick forests of cattails, willows, rabbit brush and Bullberry and Gooseberry bushes where one could have total privacy for hours on end. This length of river I knew so intimately was no more than four or five miles as the water flows, but oh what adventures it provided: half a dozen swimming holes, high banks for diving, fishing holes at the Black Knolls, a jungle like area below the rapids just right for acting out Tarzan of the apes, duck hunting areas, pelican roosts and, of course, miles of water-ways for rafts and small boats!

Rafting down the river was always one of our favorite summertime activities. Raft building was always a team project involving at least five or six guys. My older cousins, Sned and Stinky, were usually the bosses and told the rest of us what to do – where to find the logs and cross planks and how to fasten them together with whatever we could find in the way of rope or wire. And of course we needed a mast with a flag at the top, usually with skull and crossbones. The goal was to build a raft which would carry the whole crew down the river, with either Sned or Stinky serving as captain.

At the launching we would all hop on board and proudly shove out into midstream with all the hoopla you can imagine. Most often we imagined we were pirates off to plunder the world! Quite often, however, once we reached midstream, the captain would have to reorganize the crew. The craft would simply not support us all, so the captain would have to sacrifice some of the crew to the cold, deep water in order to stay afloat. You can’t imagine the disappointment at being pushed overboard after having labored so hard to construct our raft.

Another disappointment often befalling the lowly crew had to do with being scraped off the craft by barbed wire. This was actually much worse than being pushed off by the captain, because barbed wire can leave an ugly wound. You see, the farmers would string barbed wire across the river to keep their cows from invading each other’s territory, and our raft would have to pass beneath these treacherous strands. The bigger guys could usually step over them or slide under them while others propped them up. But we smaller ones would often chicken out and cower to the back of the raft until we were inevitably scraped off. Running home, cold and wet in drenched and torn clothes, with bleeding scratches underneath, caused many of us to promise scolding mothers we would never go near that damned river again. But of course we did. It was an adventure we couldn’t resist. Rafting, after all, was one of our great adventures. This was especially true when we actually survived the whole trip, with full crew, from the point of launch upstream to the Vermillion reservoir downstream. I”m sure the banks of that reservoir are still littered with logs and planks from those rafts. Some may even have my initials on them.

Of course, another favorite activity made possible by the river was swimming. Different groups of boys and girls, and pairs of lovers, had no trouble finding their own private swimming holes, but the most challenging hole of all was called the “tubes”. This was a swimming hole just below the Vermillion Reservoir, at a place called Pelican Point because of the large number of pelicans there. This was a spot where the water was released through the dam above into the narrow river below. The water, under a great head of pressure, came through huge ducts (the “tubes”) located on the bottom of the reservoir, into the narrow river, and produced a very large boiling effect with strong currents which could toss you around like a cork. It was a real thrill to dive from above into that fiercely boiling water and feel the strong currents toss you into the air above and then carry you swiftly downstream. It was considered quite dangerous to swim there , especially for little kids, and I was often rather scared when we went swimming there, but I don’t remember anyone ever drowning.

Another sport made special by the river was duck hunting. Of course we could always hike along the banks of the river and shoot ducks in flight when they took off as we approached. But we also developed a more subtle method: my father had an aluminum rowboat which my friends and I would use to shoot from as we floated very quietly down the river. We would camouflage the boat with branches and lie hidden in the prow as we floated slowly downstream. If we were quiet enough we could often float almost in amongst the ducks before they became suspicious enough to take flight. Many a family had duck for dinner after one of those excursions. Through such experiences, most kids in town became quite good hunters. And in those days hunting was never just for sport. Whatever game we hunted and killed – ducks, geese, pheasants, quail, deer, elk – was expected to add measurably to the family larder and thus enrich the family diet.

Some of the ponds, slews and marshes connected to the river provided still another challenge: spearing carp. Carp were very numerous in some of these shallow ponds and slews and often very big, so that they could be easily seen near the surface. We would take our clothes off and then wade out through muddy water with pitch forks in hand. We would spear the largest ones as their backs protruded above the surface of the water. What happened to these carp? We never ate them. I never knew anyone in town who ever ate carp. For some unknown reason they were not considered fit for human consumption. Knowing now how good they are in many European dishes, I often think about how many delicious dinners we missed. What we did with them was feed them to the pigs as a rich source of protein! There was also a downside to these carp spearing expeditions, although it didn’t keep us from going time and time again. These ponds and slews were also favorite homes for leeches or bloodsuckers! If you saw the movie, “the African Queen”, you know what it looks like to have your body covered with leeches. But if you had come carp spearing with us, you’d also know what it feels like! However, we didn’t get the fever or anything else that I know of, perhaps because we pulled the leeches off so quickly and frequently!

For two of my friends and me, the river also provided a trapping experience. During one winter we were going to make a fortune trapping muskrats and selling the fur pelts to coat manufacturers. We scouted out the muskrat dens along the river in the summer and then laid the traps in the winter. It was very cold that winter and we nearly froze setting and collecting the traps. However, we did catch quite a few muskrats and we skinned them and saved the pelts. But, we had misjudged the market and couldn’t find a buyer. Finally the uncle of one of my friends gave us a few dollars and took them off our hands. We never did know whether he was just kind or a very shrewd trader. That experience was sort of a prototype for many of our money making schemes! We were certainly enriched by our river, but we were not rich otherwise.

The Sevier River in Sigurd

Chapter 6:

THE HILLS WERE ALIVE – WITH KIDS!

In Sigurd you couldn’t look in any direction without seeing hills, hills merging into mountains. And when it came to having outdoor fun, these hills had only the river as a strong competitor for our attention.

Shale Hill was northeast of Sigurd across Brine Creek, on the south side of Highway 24 as it headed up the canyon, and was one of our favorite playgrounds. There was a small, shallow cave near the summit which could provide shelter for three or four of us, whether during a picnic or when seeking shelter from a cloudburst. To get to it we had to climb a very steep slope covered with shale. Shale is a very hard, irregularly shaped gravel-like rock consisting of pieces about one-quarter to one-half inch thick, several inches wide and with very jagged, sharp edges. It was really a tough slope to climb because of the loose shale, so that you’d take two steps up then slip back one, then two more up and fall back another, and so on.

But, we soon found a good reason to like those slippery slopes; they provided a thrilling downhill sliding area, even better than snow and available even in the summertime. Of course you needed something very sturdy to slide on because the shale was very sharp and could cause great damage to clothes and skin. However, on the hike up to Shale Hill you had to pass by the town dump, a veritable treasurehouse containing a rich selection of sliding materials. There were all shapes of metal washtubs, some with heavy lids, and old car parts such as fenders and hoods. Some of these made very good slides and could often be bent to resemble a crude boat, and in such a way that one could even steer them, after a fashion, by leaning to or fro at the right moment. To ride one of these down the shale slopes was really a thrill, gaining speed all the way down and accompanied by loud clattering and lots of sparks, especially as darkness fell across the slope. However, it was also somewhat dangerous. There were more than a few casualties, and tincture of iodine bottles came out in most houses when we returned home in the evening after one of these outings. I can still see some of my scars acquired at shale hill. But, we all went back time and time again. After all the one with the most scars got looked up to more than the others!

The big black hill above the mill was a favorite spot for playing “Cowboys and Indians”, and sometimes the hill seemed to be swarming with kids on horseback. There were also a couple of abandoned mines which were interesting to explore. There was an old copper mine which tunneled for about two hundred yards into the hill with numerous side channels leading off the main tunnel. We used to explore it using torches, which too often blew out. It wasn’t uncommon for some of the smaller kids to get lost in there, and become very frightened. We always managed to find them by following their cries, however. There was also a much shorter tunnel which we called the “soap mine” because the stones on the side of its walls had the slippery feeling of soap. I never did find out what its ore consisted of, but it provided another good play area, less scary for the younger kids.

It was also great fun to hike all the way to the top of the big black hill to get a grand view of the valley below. The houses looked tiny and the neatly laid out fields made the valley resemble a huge quilt. Max Andersen and I used to hike up there with our picnic lunches, and then spend hours trying to identify places on the valley floor.

The two black knolls are much smaller than most of the surrounding hills, but were especially interesting to explore because of the many Indian artifacts, including arrowheads and picture writing on the rocks. The knolls had the appearance of huge mounds of large black rocks with only small shrubs and brush growing between them. At one time it was rumored that they were really Indian burial grounds, but they seemed much too huge for that. They were rather dangerous because they were home to quite a few rattlesnakes, and many parents warned their kids to stay away. But, most of the kids went there anyway. Actually, we were quite knowledgeable about rattlesnakes and always very cautious when we knew they were in the area. Also their characteristic rattle warns you before they strike. Local gossip maintained that they were blind in the month of August and because they couldn’t see enemies would not emit the warning rattle, and were therefore more dangerous then.

The mild slopes on the west side of town lead up to the striking vermilion mountains which appear slit by the mouth and sides of South Canyon. This is rugged country, and the winding canyon with its very tall and steep walls stretches for miles back into the mountains. I always felt rather threatened when I was a mile or two into that canyon. You couldn’t see what was coming ahead, and the high cliffs on either side looked as though they could come tumbling down on you at any moment. Sometimes we would try to scale those steep cliffs in an attempt to reach an eagle’s nest. We were really attempting to do mountain climbing without any of the required equipment. It was sheer foolishness!

A very real risk of hiking very far up South Canyon was the danger of being trapped in a raging flood. Severe thunderstorms occur very suddenly and often high up in the mountains and may be too far away to be seen or heard from the canyon floor. And when a heavy shower funnels into a canyon like that the water quickly fills the canyon and comes down with a roar very, very rapidly. If you are alert and forewarned about such a danger, you will hear the roar and start climbing in time to reach high ground before the wall of water arrives. From such high ground I have seen what damage such a ferocious wall of water can do. Huge boulders and trees are swept down the canyon and scattered around the mouth of the canyon like so many toys. On rare occasions when the storm is big enough, the water keeps on flowing across those western slopes, across the spillways over the canals and along the canal road and cinder alley right through the center of town. South Canyon was always a little too threatening for me to enjoy it very much. Nevertheless it was a frequent hiking area for many of the kids in town.

A newspaper photograph of one of the shale hills around Sigurd

A newspaper photograph of one of the shale hills around Sigurd

Chapter 7:

LESSONS ON SWEARING, CHEWING TOBACCO AND SMOKING CEDAR BARK

Many of the lessons one learns while growing up become permanently etched in memory for one reason or another. Of course many of the lessons learned are not good, some are looked on as sinful, especially by parents, and some may even lead to vices. I remember three of my growing up lessons because of their special consequences.

The first was when I learned how to swear, I mean really swear like an adult. I was a preschooler, as were my two friends, Shan and Shar, who were cousins in the Jorgensen clan. We three were often together, in and out of mischief, like the three stooges. We even looked like the three stooges; in one photo we were all sitting in a little red wagon, with me in the middle. My dad used to cut my hair with a bowl upside down on my head, and so I looked just like Moe!

One day the three of us were playing at the Jorgensen Ranch, where Shar’s family lived, and we got tired of pretending that we were exploring outer space in our rocket ship (the top of an old metal granary) and decided to tell stories instead. So we settled down behind the barn and started telling each other stories. After trading all kinds of experiences, we got around to telling each other new things we had learned about, like new swear words. We did pretty well. Between us we new all the words for taking the Lord’s name in vain, and also most of the four letter words expressing human functions and the relations between the sexes.

We were practicing our swear words with a great deal of joy, when, all of a sudden, Shar’s mom rounded the corner of the barn swinging a big broom and headed straight toward us. I think she may have even been shouting a few swear words we hadn’t yet learned! She quickly let us know we were not behaving the way we were supposed to behave and that our fathers would hear all about it. With that threat, Shan and I took off on a dead run down the dirt road, under the railroad tracks, past the cemetery, across the canal toward the center of Sigurd and what we hoped was safety. And it was, but only for a short time.

Before dinner my dad gave me a lengthy tongue lashing about the evils of swearing. I don’t know what happened to Shar and Shan, because we never discussed it. We also never returned to our swearing lesson! In all fairness, however, I must admit that in the years to come we did add to our vulgar and profane slang vocabulary. One could hardly grow up in the midst of a bunch of hardy, robust farmers and ranchers not long descended from pioneer stock, without learning a lot of words and expressions which would probably shock a group of mixed seniors, even today. They often had to do with sex, but in this environment you could see sex live in the barnyard, and sometimes in the hay stack, almost every day. But a lot of them were also politically and socially incorrect in todays terminology. Anyway, I did learn how to swear, but it has never been very useful.

For me, a second memorable lesson had to do with chewing tobacco. My older cousins, Sned and Stinky, were always teaching me new tricks, and this is one I never wanted to repeat. We were fishing at the Black Knolls, when Sned took out a wad of chewing tobacco and bit off a chunk and then passed it to Stinky who also took a big bite. They ignored me for quite a few minutes as they chewed and spat, but I was sure watching them. I was sure I was missing something good that they didn’t want to share with me. Finally, Sned looked at me and asked if I wanted to try a plug of chewing tobacco. I nodded eagerly and he passed the wad to me. I took a big bite and began to chew, but Sned quickly warned me to chew slowly and spit out the juice and to be very careful not to swallow any. Stinky nodded and said, “God no, don’t ever swallow it, or it will finish you for sure!”, and he spat a large mouthful of dark brown juice in my direction. I wondered what was so bad about swallowing it, since it didn’t really taste bad. But, I chewed slowly and was careful to spit out the juice as it formed. However, a few minutes later I felt a strong tug on my fishing pole and my line went shooting out toward midstream. Jesus, I thought, I must have hooked a whopper! But then, guess what? Yup! I swallowed that whole goddamned plug of chewing tobacco! At first I didn’t even think about it, not until I had spent many exciting minutes landing a huge carp. But then I realized what I had done and I began to get scared. Also, I was not feeling very good. Finally, I got up the courage to tell Sned what had happened, and he jumped up, slammed his pole down, ran over to me, told me to open my mouth and stuck his finger way down my throat. I gagged and retched, but nothing came up. He wanted to make me vomit, of course, but I didn’t, even though I felt sicker by the minute. Stinky said he had heard that milk was good to take if you got poisoned, so they decided to rush me back to town where they could give me milk. We had come to the Black Knolls on horseback, so we quickly got on our horses, bareback of course, and galloped toward town. I felt so dizzy I was afraid I’d fall off, but Sned and Stinky rode on either side of me holding me on. We decided to stop at the Standard Oil gas station where there was less chance of bumping into relatives or close friends. The station didn’t have milk but they had plenty of ice cream bars – what we used to call “milk nickels”, ice cream coated with chocolate on a stick. Sned and Stinky began forcing me to eat the ice cream bars, one after the other. And finally, I really did get sick to my stomach and I vomited all over the field in back of the station. Then they made me walk and walk and walk in the cool evening air until they finally felt it was safe to let me go home. As far as I know neither my folks nor theirs ever knew about my tobacco chewing experience. I was very happy to leave it that way. And I never, ever chewed tobacco again.

However, I cannot say the same for my smoking experiences. In the early days, or the later years of elementary school, we nearly always turned to cedar bark when we wanted to be daring and try out our smoking skills. Sometimes we used corn silk or a weed called Indian tobacco, but usually we used cedar bark, rolled and crushed between our palms, then wrapped in newspaper to make cigarettes. When first lighted they tended to flame up quite a bit, leaving scorched eyebrows as evidence of what had been going on. In early summer when we returned home for dinner after an afternoon down by the river, one of the first things our mothers would do is inspect our hair and our eyebrows. If our hair was wet we caught holy hell for swimming before it was warm enough, and if our eyebrows were singed we caught even worse hell for smoking. The latter was the worse offense because Mormons were forbidden to use tobacco, and I always assumed that also covered cedar bark. Later, in junior high and high school, we would sometimes smoke our hand-rolled cigarettes made from real tobaccos – Bull Durham, Velvet, Prince Albert and Raleigh. I’m sure those early dare-devil experiences helped some of us to get hooked on Camels, Chesterfields and Lucky Strikes by the time the war came along. It was a lot harder to stop than to start, even though cedar bark really made a foul tasting smoke!

Chapter 8:

THE RED ANTS AND THE BLACK DOTS

There were two sugar beet dumps in Sigurd, one on either side of U.S. Highway 89 which ran through the middle of town. The one on the east side was headquarters for the Red Ants and the one on the west side was head quarters for the Black Dots. You could tell which was which by the flags flying on top. I don’t know why people tend to associate gangs with densely populated inner city ghettos, but, let me tell you, we certainly had them in Sigurd. And Sigurd is certainly not what you’d call a large town, with its 300 or so people.

However, there did seem to be plenty of spirited kids in Sigurd. Some were mean spirited and some were just spirited – or perhaps I should say spiritual. There did seem to be a real difference between the kids in Bishoptown and Gurrville – in the north and south ends of town – and those of us in the middle of town. A Mormon-like characterization would be that the ones in the middle of town were Jack Mormons, while those in the two ends were real Mormons. I can’t speak for those in the ends, but those in the middle, the mean spirited ones, had lots of imagination when it came to playing games. And the contest between the Red Ants and the Black Dots was only one such game.

I think it was the brain child of Stinky Barron and Garth Nielsen, who were cousins, but generally disposed to be on opposing sides of almost any issue. Their different views often led to fist fights or no-holds-barred wrestling. They were both in their teens and a few years older than most of the rest of us. Anyway Stinky Barron was the head of the Red Ants and Garth Nielsen was the head of the Black Dots, and the rest of us wound up as members of one or the other of these gangs. As I remember, there were about seven or eight kids in each gang. I wound up in the Red Ants, perhaps because Stinky Barron was also one of my cousins, and I was not related to Garth. The names of some of the other kids in my gang were Shan and Shar Jorgensen, Hal Anderson, Tex Barron, and Iral Colby. The “game” lasted all through the summer and proved to be an unforgettable experience.

First, a word of explanation about three things: our club houses, our treasures and the plot. We didn’t need to build club houses because the beet dumps provided them ready-made. At the time, sugar beets were the main cash crops in Sevier County, and the beet dumps were tall wooden

structures beside the railroad tracks and contained a weighing platform, escalators for transferring the sugar beets from wagons to box cars, a set of stairs and a little room on top to house the two man crew. They were only in use at harvest time in the fall, so in the summer they were perfect club houses for our gangs. There was even a place at the very top of them where we could fasten our flag poles, so nearly the whole town could see our flags, one with a drawing of a big red ant in the center and one with a big black dot.

Each gang’s treasure consisted of a Mason jar filled with money, earned by the members of the gang contracting with farmers to thin their sugar beets. This was a very common way for kids to earn money during the first part of summer. The treasure for each gang was then buried by the head of the gang in a secret location, either in the foot hills above town or along the Sevier river which wound it’s way along the east of town between the gypsum mill and the Vermillion reservoir. A map was made showing the location of the buried treasure, and then each member of the gang got a piece of it to keep.

The plot or contest was to see which gang would be first to find and plunder the other’s treasure. Anything was fair, including spying on the chiefs to see in which direction they headed when they went out to bury the treasure, and various tactics to get a member of the enemy gang to give up his portion of the map, including bribery, threatened torture or a promise to split the stolen treasure.

Within our own gang we had lots of fun together, playing keepers marbles, hiking, swimming, horseback riding, sleeping outside rolled up in quilts on each other’s lawns, hunting jack rabbits in the sagebrush flats, roasting potatoes around a bonfire at night, and all sorts of other things. But the real excitement came when we would come face to face with our enemies, the Black Dots! Nearly always such a meeting would lead to a fight. It was a real battle all right, but our system of warfare was, as I learned much later, much like that suggested by one of the German soldiers in Erich Remarque’s novel, “All Quiet On The Western Front”, wherein the leaders were to be put into a ring and told to fight until one of them surrendered and lost the war for his side.

Thus, we ordinary, cowardly members of the gangs would usually stand back and let Stinky and Garth go at each other. Lordy how they could fight! Although Garth never said “I surrender”, Stinky did usually seem to be the winner. He was the meaner fighter of the two, as was fitting for his nickname. He was called Stinky ever after being doused with perfume in school. However, the name was also appropriate for another reason: he was often very nasty. Anyway Garth wouldn’t give up and so they would simply fight until they were tired out and then the fight would stop and the gangs would part in silence, until the next time.

By other means though, the Red Ants did manage to triumph, thanks mainly to a strategy developed by Stinky. We would patiently bide our time until a group of us could catch the Black Dots, one at a time, going home alone, either from the Meeting House or the general store, or working alone in one of the fields beyond earshot of their house. We would then take our prisoner to our beet dump and explore ways to get him to fork over his piece of the Black Dot’s treasure map. Methods that worked best included the threat of torture and the promise of reward for turning traitor. The younger enemies would turn over their piece of the map as soon as asked, even before a threat or offer, and then run like hell toward home as soon as they were turned loose. Some of the older enemies, though, would pretend bravery and patriotism up to a point, but would finally give in. I can still see Bill starting to cry when we took off his shoe and Stinky pointed a burning stick toward his bare foot. Anyway, without dwelling on all the gory details, we finally got all of the pieces of their map, except Garth’s. As far as I know our gang lost only one piece, that given up by Iral who was unlucky enough to be caught alone in back of his father’s corral. Iral was the least militant in our gang and quite easily frightened.

Even though we had gotten, by hook or by crook, all except one piece of the Black Dot treasure map, we could not find the treasure. The pieces of the map we had indicated that it was buried somewhere along the river as it approached the reservoir, but we searched high and low for it without any luck and finally gave up. So, the summer ended and we never did see the Black Dot treasure. Come to think of it, we ordinary members never saw the Red Ant treasure again either! I suspect Stinky and Garth each had a good time spending their treasures, but at least the rest of us didn’t have to fight.

One final note about gangs in Sigurd. Neither the Red Ants nor the Black Dots ever experienced a casualty, not even a serious wound. This may be all the more remarkable in view of the fact that each kid had a gun, usually a twenty-two, and knew how to use it well enough to shoot jack rabbits. If you’ve never tried to shoot a jack rabbit, try it sometime; it’s very difficult. Also if you were to walk through Sigurd you wouldn’t see a single policeman. We did have a town marshal in plain clothes, Fred Nielsen, who was Garth’s father. He was a wonderful man who stacked hay for Jack MacMillan; he was probably the best hay stacker in the county, but as Town Marshal of Sigurd, he never arrested anyone.

Chapter 9:

COLORADO INTERLUDE

In 1929 my father, under pressure from his father to join him in a very sizable sheep ranching business in Colorado, sold his ranch in Grass Valley and moved his sheep to Colorado to join in partnership with my grandfather. As it turned out this was not a good year to do this, for financial reasons, and my grandfather, with his very demanding ways, was not an easy person to be in partnership with. He always seemed to take more than he gave in such a venture.

Nevertheless, it provided a very interesting interlude, from our life in Sigurd, for my sisters and me during the summers between 1929 and 1931. During this period we spent our summers in the mountains of Colorado with my father and his sheep, although the winters were still spent in Sigurd. For me, from the age of five and a half to eight years, it was like paradise! I had my own horse, Juana, a beautiful sorrel mare – the colt of my big bay mare in Grass Valley – to ride whenever I wanted, my own 410 gauge shotgun with which to hunt grouse and sage hens (poaching of course), and a whole Rocky Mountain range to have fun in. Mountain lakes were great for swimming, despite a few leeches or blood suckers, and both the lakes and streams were good for fishing. Even my chores were fun: to provide fresh fish and game as a welcome addition to our usual diet of mutton, homemade sour dough biscuits, canned evaporated milk, which I hated, and canned fruits and vegetables. The only chore I didn’t look forward to was tending my younger sisters, a job which I sometimes did very poorly, as you’ll soon see.

In going to Colorado for those memorable summers, the routine was something like the following. With the beginning of summer my grandfather would come to Sigurd in his car, (the one I remember best was a new Model A Ford sedan), and then drive my mother and my sisters and me to Colorado. This took over two days and we would stop at night at an auto court and stay in a small cabin. We’d have a late dinner, usually some bread and pork’n’beans out of the can, and then go to bed. I dreaded those nights, because I had to sleep with my grandfather. He was a very big man, well over six feet tall and weighing more than 200 pounds, and whenever he rolled over I would get crushed!

My grandfather Sevy was not very sensitive about others’ feelings, as I learned repeatedly. One time my sister Ruth and I rode with him up a mountain road to meet my father near one of their large sheep herds. He drove as far as the road would take us and then had to hike a mile or so up the trail to where the herd was. As he left the car he slammed one of those Model A doors on my thumb and left me trapped in that condition for well over an hour while he went off to check on the sheep. The door was locked, so my sister, Ruth, could not get me loose. My mother was furious with my grandfather for this, and I think she never forgave him. My thumb was black and blue for a long time and I lost the nail, but I eventually recovered.

Our first destination in Colorado, where we joined my father, was the Mountain Meadow Ranch where the sheep were collected early in the spring before beginning their trek up the mountain, and also in the late fall after coming down off the mountain. After we arrived there we would spend only a few days at the ranch, where my sister Ruth and I enjoyed playing among all the corrals and sheds surrounding the large, old stone house we lived in, and then we would move part way up the mountain to our first campsite, my favorite place during those wonderful summers in Colorado.

The system for managing the sheep was to have the sheep graze up the mountain following the seasonal growth of the grass, reaching the peak of the mountain about mid-summer, and then to start them grazing down the mountain after the grass had a chance to grow up again. One time on the way down they were caught in a heavy snowfall before they reached the valley floor, and, in addition to the loss of many sheep, my father lost a horse and very nearly himself in a deep ravine filled with snow. However, this system of grazing up the mountain from the Mountain Meadow Ranch in the spring and then back down in the late fall generally worked very well. The Mountain Meadow Ranch was not far from the town of Craig, and even nearer to a whistle stop junction named Hamilton, consisting of a General Store and a couple of houses. Craig and Hamilton were the main sources of our supplies while we were on the mountain. Our mountain was in the area my father referred to as the Morapus Creek Forest.

We could reach our first or base campsite on the mountain by driving up a winding, rocky dirt road in my father’s pick-up truck loaded with our tents, stoves, grub boxes, quilts and other equipment. Many of our supplies were also brought up with pack horses. Once there, our first job, of course, was to set up camp. This to me was a very exciting process. First, we would locate the most level spots to pitch our large, heavy canvas tents. Then the tents would go up like magic! My father was truly an expert at this. After the tents were pitched we built the beds, a large one in the back half of each tent. The bed frames were made with fresh aspen logs, notched to make a rectangle. The springs were made of fresh pine boughs piled inside the frame of aspen logs. The pine boughs were then covered with a thick canvas, and on top of this we made the bed with homemade quilts and big stuffed pillows. My parents slept in the largest of the two tents, containing the stove and grub boxes, while my sisters and I slept in the other tent, along with stored supplies and one or more sheep dogs.

Next the camp stoves were set up, one with a chimney inside my parent’s tent, in case of rain, and one outside. Grub boxes were located both inside and outside, depending on their contents. Suitcases and duffel bags were placed inside. Tables, benches and chairs were homemade of aspen logs. Even the outhouse, located beyond smelling distance, was a bench constructed with aspen poles stretched across a rather deep pit. Toilet paper was a mail order catalog. A long hammock was tied between two large aspens, and my mother’s hand-wound phonograph was usually placed near it on a platform of rocks. She also kept a box of books and magazines within easy reach of the hammock.

About a hundred yards or so up the mountain from our camp site there was a little, half-collapsed, abandoned cabin, probably the original reason for the dirt road to the area of our campsite. Beside it was a little overgrown garden plot, which my mother resurrected and used to plant a few rows of lettuce, radishes and green onions. This was a blessing for her, because she loved salads and fresh vegetables. In Sigurd her supper often consisted of bread and butter with water cress and green onions. Our base camp was within easy hiking distance of a beautiful little mountain lake which we used for bathing as well as swimming. The water was indeed quite cold, but we seemed to get used to it. There were also a few leeches in the lake, but we weren’t bothered by them too much. On the other hand they elicited a few screams from guests who came to visit on rare occasions. There was also a beautiful rushing creek very near our campsite, providing plenty of water. We were also surrounded by a beautiful forest. There was an abundance of huge pine trees towering above the groves of aspen, and the floor of the forest seemed covered by ferns which reached as high as a horse’s belly. There were also plenty of wild flowers, berries and other plants.

Deer and grouse were plentiful and the rushing mountain streams were full of trout. Each species furnished our table with food on more than one occasion. The meals cooked on our camp stoves were always a great treat. My mom was a terrific cook no matter what the stove. The only meal I did not look forward to was breakfast. It was usually cold cereal with that awful canned evaporated milk! But the biscuits were always good. My father was in charge of the bread making, and it was always sourdough biscuits, made from a “start” of sourdough we carried with us whenever we moved. Such was life at our base campsite in Colorado. To me it became unforgettable.

The base camp was where we spent most of our time while on the mountain, since we lived there during a good part of both the upward and downward grazing of the sheep. During most of each day, however, my father was where the sheep were, whether above or below our campsite. A couple of times during the summer ,however, we would move up the mountain to stay at another campsite for a short while to be nearer to where the sheep were.

A move up the mountain beyond our base camp was quite a process. We used pack horses, each carrying two large packsacks, one on each side attached to the packsaddle, loaded with our supplies and equipment. My mother would ride a saddle horse, leading one of the pack horses carrying my two youngest sisters, one on each side perched on a big pillow in the packsacks. My sister, Ruth, and I would ride together on my sorrel mare, Juana, usually bareback, with me in front and Ruth behind with her arms clutching me around the waist. In this way we would move ourselves up the mountain to our new campsite.

I remember several things in favor of these higher campsites: the more spectacular view down the mountain to the valley below, the beautiful orange-red sunsets and the wild strawberries at the higher elevation. My mother especially liked the varieties of many colorful wild flowers. One plant we quickly learned to have a lot of respect for was stinging nettle! Just brushing against it caused a very painful sting, followed in minutes by the raising of severe red welts on your skin.

At both the base camp and the shorter term camps higher up, my sister Ruth and I learned to be great companions and we played together all the time. We also hiked in the forests around the camps, often going quite a long way from camp, which caused my mother no end of worry. We also rode Juana, nearly always bareback, with Ruth clutching me from behind, for even greater distances from camp. Ruth was always at a disadvantage on these rides because she could not see what was coming. On many occasions I would duck under a low lying limb only to let Ruth be swept off Juana as she galloped beneath it. Ruth still shows more than a few scars from those adventures.

Ruth and I made up all sorts of games to play during these long summer days, and generally had a great time together. Our younger sister, Gerry, on the other hand, did not fare so well because Ruth and I did not often include her in our adventures and games. Of course Gerry was only two years old at the time of our first summer in Colorado! Ruth and I were sometimes charged with tending Gerry, but, as baby-sitters, age five and a half and four, we were not all that reliable. Once while “tending” her we let her wander into a patch of stinging nettle where she was very badly stung. She developed a high fever and was very sick, and Dad had to go to Craig to fetch a doctor to see her. The Doctor said she had a very bad case of stinging nettle fever, and we were all afraid she might not recover. She did recover, however, only to come close to suffering a worse fate later on, thanks to Ruth and me as we once again failed our baby-sitting chores. Mom, Gerry and Ruth and I had left our base camp late one afternoon to accompany Dad up the mountain to bed down the sheep for the night. We had come to a grassy clearing beside a creek which Dad decided would be a good place for us to rest and play while he went a little farther on to bed the sheep. He showed Mom a good place to sit and read on a big rock by the creek, and told Ruth and me to stay within the clearing while we played, and to make sure we watched after Gerry and to keep her from going near the creek. Well, all went according to plan except for watching after Gerry. While Ruth and I were playing, she wandered out of the clearing into the forest and we didn’t notice that she was gone. When Dad returned there was no sign of Gerry and no response to our calling her. Dad was furious! He was very angry with Mom, but especially with Ruth and me whom he had lectured very sternly about looking after Gerry.

Now, we had arrived at the clearing by way of an old logging road which had crossed the creek about a quarter mile before the clearing. Dad quickly decided that the creek was the biggest danger to Gerry, and that if she knew she was lost, she might try to find her way back “home” along that old road which crossed the creek. And where the road crossed it, the creek was about a foot and a half deep and very swift! So, within a few seconds after Dad’s return to the clearing, he sent me running to the creek to search along it toward the crossing, while he took off like a bullet to reach the crossing by the road. Sure enough, young as she was, Gerry had realized she was lost and set out to find the road by which we had crossed the creek on our way to the clearing. When Dad reached the crossing, there was Gerry sitting on the creek bank, taking off her shoes before wading across the creek. Had she attempted to wade it, she would surely have been swept downstream by the swift current. We were all so thankful when Dad called out that he had found her! We hardly spoke a word on our way back to camp. Mom was crying, Dad was hugging Gerry and I was nursing all the scratches I acquired running through the brush along that creek. I think the lesson Ruth and I took from that frightful experience has stayed with us to the present day. I do not remember Mom or Dad ever having to scold us again for not looking out for the welfare of our younger sisters. Nowadays, it may seem wrong to have entrusted baby-sitting chores to such youngsters, but it was not unusual nor wrong in those days under those circumstances.

It was very good that Ruth and I learned to play so well together, because we seldom came in contact with any other playmates. There was a family named Carrigan who lived in a log cabin a few miles down the mountain. Mr. Carrigan ran an old sawmill. They had a son, Billy, a couple of years older than I, and sometimes he would hike up to play with me, and sometimes I would go down there. When I did, I’d always try to get there at breakfast time, because Mrs. Carrigan made excellent flapjacks for breakfast. But, except for the Carrigans, there were hardly any other neighbors for miles around our camp site, and thus a scarcity of playmates.

Once, however, in 1931, three families from Sigurd formed a caravan and drove all the way to Colorado to spend about a week visiting us. They were the Barrons, the Jorgensens and the Andersons, and each family had several kids. My father said that all told there were sixteen of them, including my cousin Sned (Leone Snedegar) who rode with my Uncle Bill Barron and his family. With sixteen of them and six of us (I had a new little sister named Jo Anne by then) we were a large group to have to feed by cooking on two little camp stoves! Oh, but Ruth and I were so happy to have all those kids to play with!

The three visiting families from Sigurd pitched their tents next to ours, so we formed quite a colony. The littlest kids got lost on numerous occasions, but we always found them. A few kids got stung by bees around the camp, and more got stung by the stinging nettle, but none were seriously injured. Once, my Uncle Bill wiped his behind with the nettle after going to the toilet. You can bet your life he never did that again! My cousin Sned slipped and fell into some dog-do while we were playing a game of tag, and had to sit in the tent the rest of the day until his Levis dried, after Aunt Verda washed them. The older kids really enjoyed the hiking, riding, fishing and swimming. Some of them also wanted to go hunting , but my Dad forbade them to go near any of the guns. He trusted me to hunt when I was alone, but not when other kids were around.

For swimming, which included bathing, we went in naked, so the adults set up the rule that the women and girls would swim at a scheduled time, and only after they returned from the lake, could the men and boys go. If we sneaked away from camp and wandered anywhere near the lake while the girls were in, and quite a few of us did, we could hear the girls screaming because of the leeches. On one occasion, the married women were swimming by themselves and the married men tried to sneak in with them, but were promptly chased away.

Meals were like a circus with such a large group. It was chuckwagon style, with the women first preparing all the food, using the two little camp stoves, then setting it up on a counter type table, and serving each of us in our tin plates and cups as we passed by. Then we would seek out a rock or log to sit on, near those we wanted to visit with during the meal. Lane Barron once picked out a spot near where the sheep dogs were resting, and when he turned his back for a few seconds, his mutton chop suddenly disappeared from his plate. I don’t recall whether or not Aunt Verda fixed him another chop, but Lane always ate at some distance from the dogs after that.